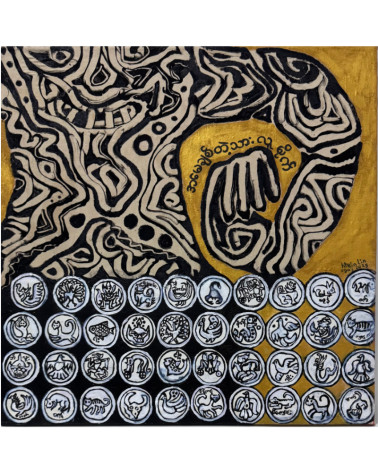

Htein Lin’s work, inked by fate and resistance, tells stories of survival and imagination behind bars. A collection of rare pieces created with makeshift tools, but shaped by clarity, intensity, and vision.

91 x 91 - 2008 - Acrylic on canvas

Retour De Voyage spoke with Burmese artist Htein Lin about his 2008 painting Me and My Tattoo — a deep dive into the world of Burmese prisons in the late 1990s, where art, ink, and pain were etched directly into the skin.

Retour De Voyage:

Your painting Me and My Tattoo is a very intimate, embodied piece. How did this relationship with tattooing begin in the prison where you were held?

Htein Lin:

When a new prisoner arrived, there was almost always this strange but symbolic invitation: “Come on, get a tattoo, come score some goals.” It was a kind of initiation, a way to be welcomed. Tattooing was a rite, a way to be seen by others. Back in 1998, tattoos weren’t popular in Myanmar like they are today. It was more of a fringe thing, associated with pagoda festivals or certain neighborhoods. But in prison, if you didn’t get tattooed, it was as if you weren’t really in. It was an invisible line, a code of belonging.

Retour De Voyage:

But you were a political prisoner. Wasn’t the tattoo culture mainly part of the world of common criminals?

Htein Lin:

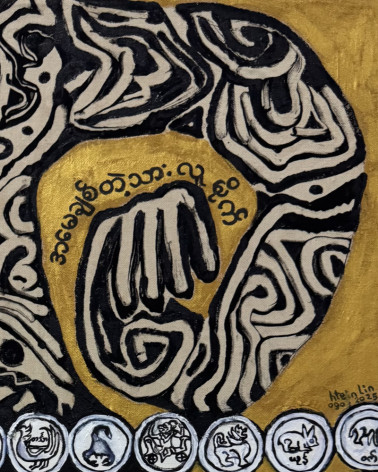

Yes, it was originally their culture. But in prison, all boundaries disappear. We lived on top of each other, we got to know each other. And you quickly learn to read bodies. Tattoos tell stories: dragons, tigers, lions, hunters, slogans… Some had “No pain, no game” or “I love my son” inked on their chest. Others had things like “I’ll drink a woman’s heart with alcohol.” You could read violence, tenderness, loneliness, and rage in them.

Retour De Voyage:

And then the others found out you were an artist. Is that when you moved from being a spectator to becoming a participant?

Htein Lin:

Exactly. The younger inmates came to me asking for drawings. They wanted me to tattoo traditional figures like Ezali, tiger hunters, monsters… But I didn’t want to copy. I didn’t even know what those models looked like. I said, “I’ll only tattoo what I invent.” And to my surprise, they liked it. They wanted something new, something real. One guy said, “I want something no one else has.” So I started drawing strange things from my imagination, sometimes inspired by Dali or other surrealist influences.

RDV:

What tools did you use to tattoo?

Htein Lin:

Almost nothing. A wooden stick, four needles tied to the end. The ink was diluted Chinese ink mixed with thanakha. Everything was improvised, like all the art I made in prison. But even with that, something got through — a line, a shape, a symbol — and that person carried a story, a pride, a bond on their skin. Some paid me with rice or soap. And sometimes, just by saying: “You gave me a dream.”

RDV:

At the end of your text, you mention a sort of shift — your drawings became emblems. Can you tell us more?

Htein Lin:

Yes. Little by little, some of my designs became popular. They showed up not just as tattoos, but also drawn in chalk on uniforms, scratched into the walls, echoed in cell poems or songs. It was like a poetic contagion. Art found its way in everywhere — even where it had no business being. That’s when I understood: even locked up, without brushes or colors, an artist can still draw a world.

RDV:

Why was the text about this painting written so much later, in 2008?

Htein Lin:

Because after I got out, I realized that no one really knew about those tattoos, those stories. Everyone was talking about politics, injustice, resistance. But the human world of prison — its codes, its pain, its dreams — remained invisible. I wrote so it wouldn’t disappear. To preserve the memory of that living skin. Skin was our memory.

RDV:

Thank you, Htein Lin, for this powerful testimony. Your voice — like your art — speaks to something essential about human dignity, even in the deepest darkness.

No customer reviews for the moment.